For most people, generic drugs are invisible. They’re the $4 pills at the pharmacy, the ones your doctor prescribes because they’re cheaper than the brand name. But behind that low price tag is a system on the brink. In 2023, generic drugs made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they accounted for just 20% of total drug spending. That sounds like a win-until you realize that 278 drugs were in short supply that year, and nearly 70% of them were generics. Millions of patients are now skipping doses, switching to more expensive brands, or going without critical medications like antibiotics, heart pills, and cancer treatments-all because the system that makes these drugs can’t keep up.

How We Got Here: The Economics of Cheap

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act was supposed to make generics affordable and widely available. It worked-too well. By allowing companies to copy brand-name drugs without repeating expensive clinical trials, it opened the floodgates for competition. But instead of stabilizing prices, it created a race to the bottom. Today, pharmacy benefit managers and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) award multi-million-dollar contracts based on price differences smaller than a tenth of a cent per tablet. If one manufacturer drops their price by $0.001 per pill, they win the contract. The next one drops it by $0.002. And so on. Generic manufacturers now operate on margins of 15-20%, and some drugs barely clear 5%. Compare that to branded drugs, which often have 70-80% gross margins. When margins shrink this thin, there’s no money left for upgrades, backups, or quality control. A single machine breakdown, a delayed shipment of an active ingredient, or an FDA inspection finding can shut down production for months. And when that happens, there’s no backup manufacturer ready to step in-because no one else can afford to make the same drug at a profit.The Global Supply Chain Is a House of Cards

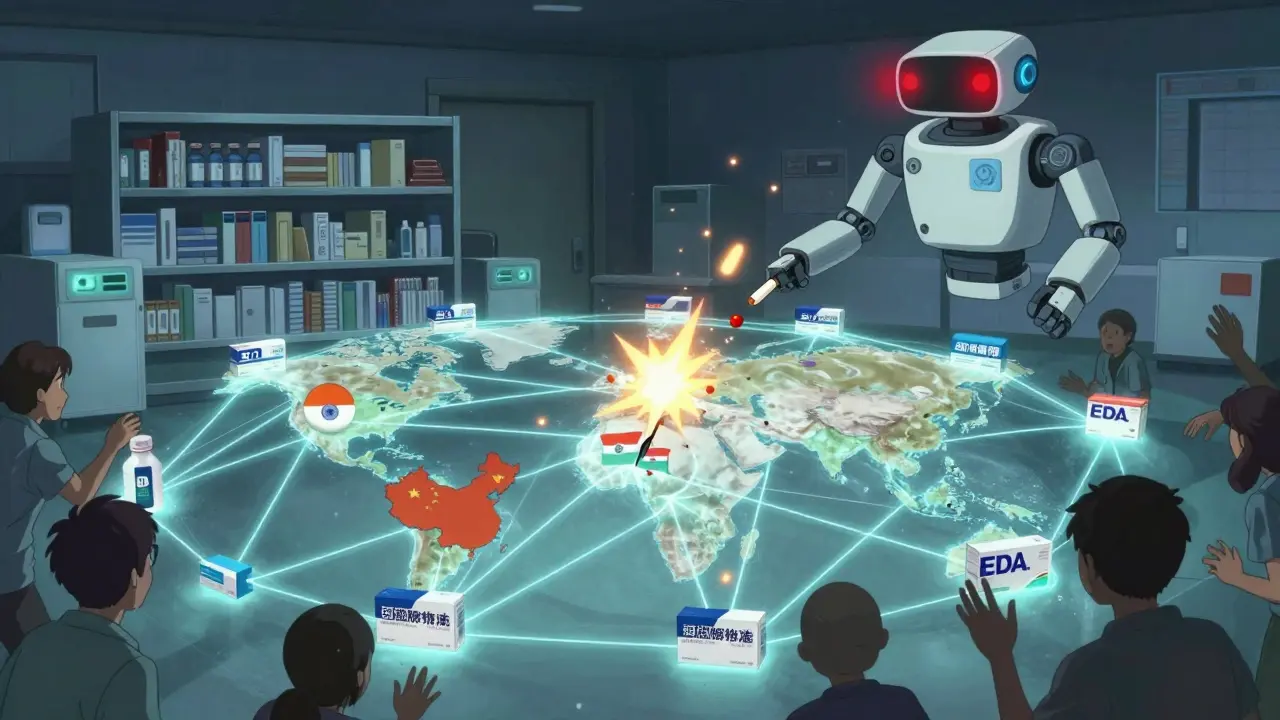

Almost all of the raw ingredients for generic drugs-called active pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs-come from just two countries: China and India. The FDA says 97% of antibiotics, 92% of antivirals, and 83% of the top 100 generic drugs in the U.S. have no domestic source for their API. That means a single factory closure in one country can trigger nationwide shortages. During the early days of the pandemic, India halted exports of 26 essential medicines, including acetaminophen. China shut down 44 pharmaceutical facilities. The U.S. didn’t have enough domestic production to fill the gap. Even now, 80% of the key chemical precursor for acetaminophen comes from China. One supply line. One disruption. One shortage. The problem isn’t just geography-it’s complexity. One drug might have its API made in India, mixed with fillers in Germany, coated in Mexico, and packaged in the Philippines. Each step adds risk. A delay in one country stalls the entire chain. And because these manufacturers aren’t required to disclose their supply chains to regulators, no one knows exactly where the next breakdown will happen.Quality Control Isn’t Optional-It’s Just Too Expensive

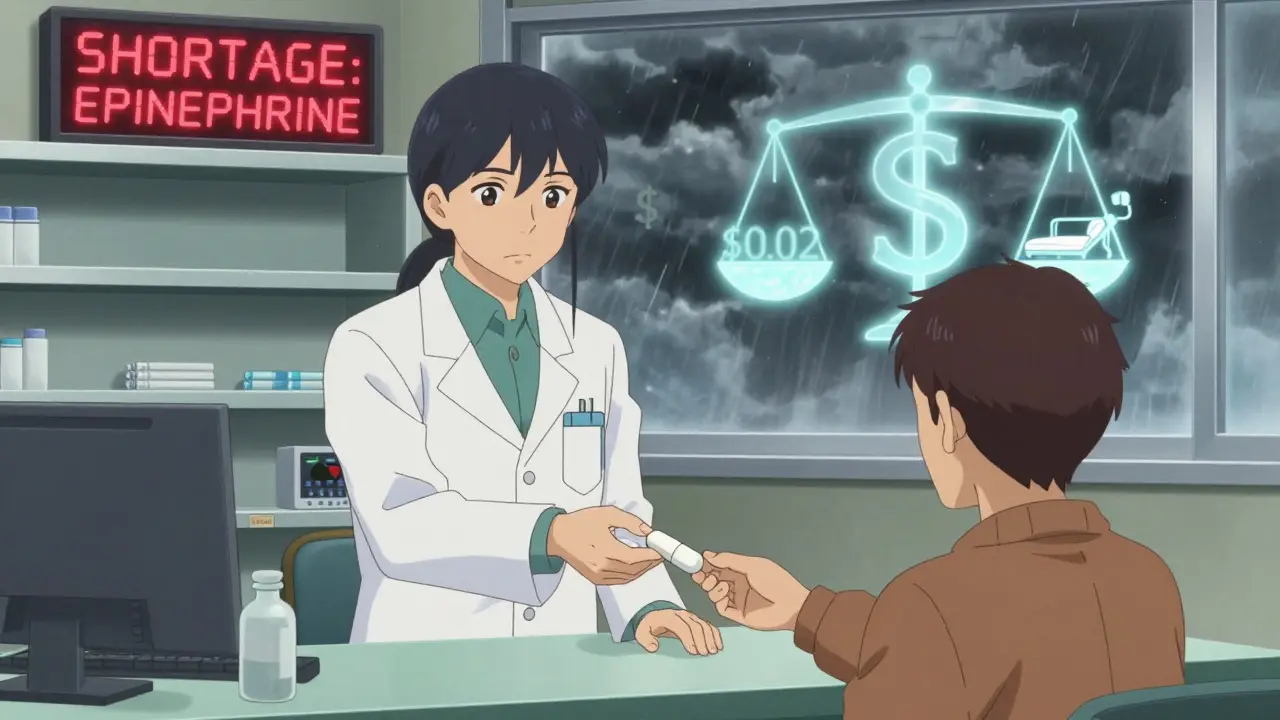

Making a generic drug isn’t just copying a pill. It’s matching the exact chemical structure, dissolution rate, and stability of the brand-name version. That requires precision. But modern manufacturing tools-like continuous production systems that monitor quality in real time-cost $50 million or more to install. Most generic companies can’t afford it. Instead, they rely on outdated batch manufacturing, which is slower, less consistent, and harder to control. The FDA found that U.S.-based manufacturers maintain 95%+ accuracy in their production records. Some foreign facilities? As low as 78%. In 2022, the FDA pulled Intas Pharmaceuticals’ cisplatin-a vital cancer drug-from the U.S. market after finding “enormous and systematic quality problems.” That wasn’t an accident. It was the result of a system that rewards the lowest bid, not the safest product. A 2023 study found that generic drugs made in India were linked to 54% more serious adverse events-including hospitalizations and deaths-than identical drugs made in the U.S. Researchers say it’s not proof of causation, but it’s a red flag. When you’re paying $0.02 per pill, you can’t afford to test every batch. You can’t afford to hire enough inspectors. You can’t afford to fix problems before they hurt people.

The Factory Shutdowns Are Already Happening

Between 2010 and 2023, the U.S. lost more than half its domestic API production capacity. In 2010, 35% of APIs were made here. Today, it’s 14%. Over the past decade, 37% of U.S.-based generic manufacturers have shut down or operate with idle equipment. The top five companies now control nearly half the market-up from 22% in 2010. That’s not competition. That’s consolidation after collapse. Akorn Pharmaceuticals, once a major generic maker, filed for bankruptcy in February 2023 and stopped producing everything. Overnight, dozens of essential drugs vanished from shelves. There were no alternative suppliers. No backup stockpiles. Just silence. New manufacturers struggle to enter the market. Setting up an FDA-compliant facility in the U.S. costs $250-500 million and takes 3-5 years. In India or China, it’s $50-100 million and takes half the time. Even if a company wants to build here, the market won’t let them. Why invest millions to make a drug that might be sold for $0.01 less than the next guy’s?Who’s Getting Hurt?

It’s not just hospitals and pharmacists. It’s patients. A nurse practitioner in Texas told Medscape she had to switch 89 patients off levothyroxine because the generic ran out. One woman on Medicare saw her monthly cost for a heart medication jump from $10 to $450 when the generic disappeared. On Reddit’s r/pharmacy, hundreds of healthcare workers shared stories: “We’ve had to switch antibiotics for 17 different infections in six months.” “No epinephrine for three weeks.” “No IV saline.” The FDA’s drug shortage portal saw complaints rise 327% between 2019 and 2022. Cancer patients, diabetics, people with epilepsy-these aren’t minor inconveniences. These are life-or-death gaps in care.

What’s Being Done? (Spoiler: Not Enough)

The FDA has a Drug Shortage Task Force. Congress passed the CREATES Act in 2019 to stop brand-name companies from blocking generic access. The Biden administration added $80 million in 2024 to inspect foreign facilities-up 12% from last year. But there are now 40% more foreign sites to inspect. The funding increase barely keeps pace. The FDA can’t force a company to make a drug. They can only call and ask. That’s it. Some states are trying to help. A few are creating state-level stockpiles of critical generics. Hospitals are bypassing GPOs and negotiating directly with manufacturers to lock in supply. But these are patches, not solutions. The real fix? Change the pricing model. Reward reliability, not just the lowest bid. Fund domestic API production with tax incentives. Require manufacturers to maintain minimum stockpiles. Allow the FDA to approve backup suppliers before shortages happen. None of that is happening yet.What This Means for You

If you take a generic drug every day, you’re already living with this risk. The next shortage could be yours. Here’s what you can do:- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this generic in short supply?” If they say yes, ask if there’s a stable alternative.

- Keep a 30-day supply on hand if possible-especially for heart, thyroid, or seizure meds.

- Know your drug’s active ingredient. If your generic runs out, you might be able to switch to another brand of the same generic.

- Report shortages to the FDA’s website. More reports = more pressure to act.

Why are generic drugs so cheap compared to brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs are cheaper because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act lets manufacturers prove their version is equivalent to the brand-name drug without redoing human studies. That cuts development costs dramatically. But because so many companies compete to make the same drug, prices are driven down until margins are razor-thin-sometimes below 5%. That’s why manufacturers can’t afford to invest in better equipment or backup supply lines.

Are generic drugs less effective than brand-name drugs?

Legally, generics must be bioequivalent to the brand-name version-meaning they work the same way in the body. But effectiveness isn’t just about chemistry. If a generic is made with poor quality control, inconsistent ingredients, or outdated equipment, it may not dissolve properly or stay stable over time. That’s why some patients report different side effects or lack of results. The FDA approves generics based on averages, not individual batch consistency. So while most generics work fine, the risk of variation is higher when production is outsourced to low-cost countries with weaker oversight.

Why don’t more companies make generics in the U.S.?

Building a U.S.-based FDA-compliant facility costs $250-500 million and takes 3-5 years. In India or China, it’s under $100 million and faster. Even if a company builds here, they can’t charge more because GPOs and PBMs demand the lowest price. So they either lose money for years trying to break even-or they don’t build at all. The market doesn’t reward safety, reliability, or domestic production-it only rewards the lowest bid.

What drugs are most likely to be in short supply?

Antibiotics, cancer drugs like cisplatin and doxorubicin, heart medications like digoxin and amiodarone, thyroid hormone (levothyroxine), epinephrine, and IV saline are among the most commonly短缺. These are all high-volume, low-margin generics. They’re cheap to make, but also cheap to buy-so manufacturers have little incentive to keep producing them reliably. Many of these drugs also rely on APIs sourced from just one or two foreign facilities, making them vulnerable to geopolitical or supply chain disruptions.

Can I switch to the brand-name drug if the generic is unavailable?

Yes, but it will cost more-sometimes hundreds of dollars more per month. Insurance often won’t cover the brand-name version unless you prove the generic didn’t work or caused side effects. Some pharmacies can order the brand-name version if you’re willing to pay out of pocket. Talk to your doctor and pharmacist. They may be able to help you get a temporary supply or apply for patient assistance programs from the manufacturer.

Is there any hope for fixing this system?

There’s growing awareness. Congress has introduced bills to tax-incentivize domestic API production and create strategic stockpiles of critical generics. The FDA’s Emerging Technology Program has approved 12 new continuous manufacturing lines since 2019-but they’re still less than 3% of total capacity. Real change requires breaking the cycle of price-only contracting. If hospitals and insurers paid for reliability-not just the lowest bid-manufacturers could afford to invest in quality, backups, and U.S. production. Until then, shortages will keep happening.