When a pharmacist hands you a bottle of generic lisinopril instead of the brand-name Zestril, it’s not just a simple swap. Behind that decision is a complex financial system that determines who pays what, who makes money, and whether you actually save anything at all. Pharmacy reimbursement isn’t about drug quality-it’s about dollars and incentives. And right now, the system is working against the very goal it claims to support: lowering drug costs.

How Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

Pharmacies don’t get paid the same way for every drug. For brand-name medications, reimbursement used to be based on the Average Wholesale Price (AWP)-a list price that often had little to do with what the pharmacy actually paid. Today, most generic drugs are reimbursed using Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists. These are hidden price ceilings set by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) that tell pharmacies the most they’ll be paid for a specific generic drug.

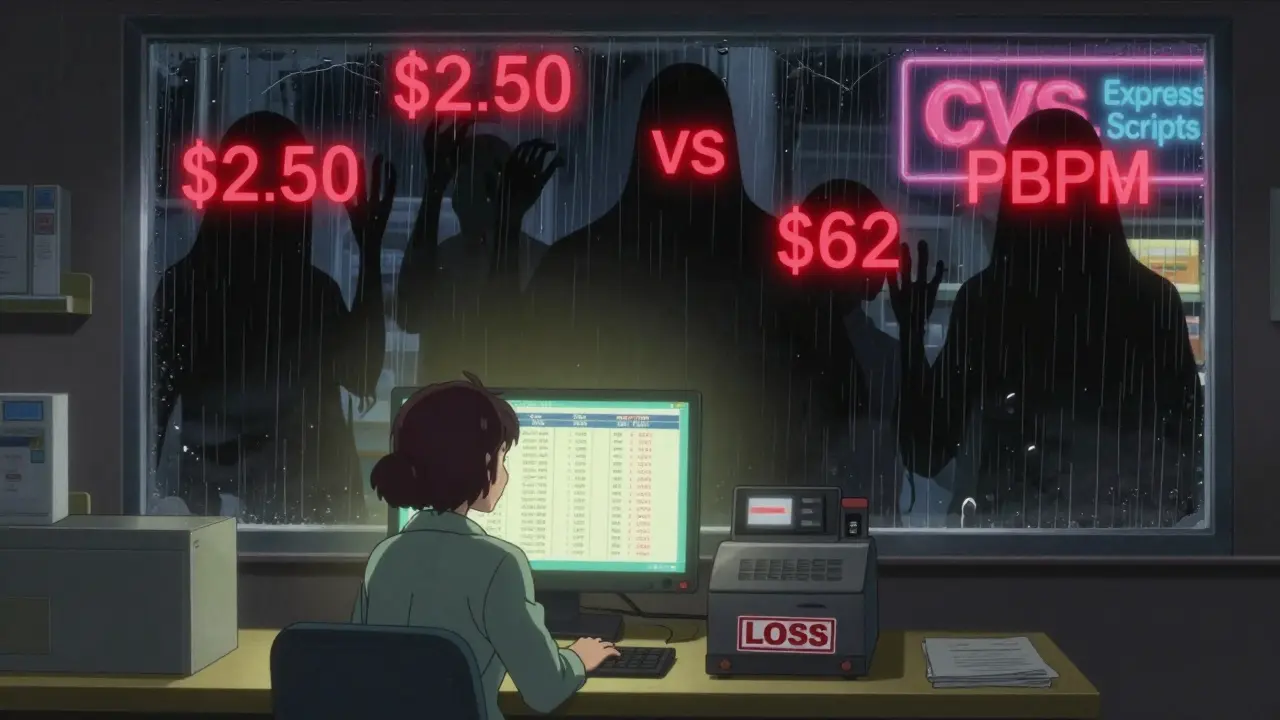

But here’s the catch: MAC lists aren’t standardized. One PBM might pay $2.50 for a 30-day supply of generic metformin. Another might pay $6.20 for the same pill. The pharmacy buys it for $1.80. So who decides the difference? The PBM. And that gap-between what the pharmacy pays and what the PBM pays-is called spread pricing.

That spread is where PBMs make money. And the higher the MAC, the bigger the spread. That’s why PBMs often push higher-priced generics onto formularies-even when cheaper, clinically identical alternatives exist. It’s not about saving patients money. It’s about maximizing profit.

The Financial Incentive to Substitute

Pharmacies make way more money on generics than on brand-name drugs. Gross margins on generics average 42.7%, compared to just 3.5% for brands. That’s a huge incentive to swap out expensive drugs for cheaper ones. But here’s the problem: if reimbursement models cap how much a pharmacy can earn per prescription, that incentive disappears.

Some payers use cost-plus reimbursement, where the pharmacy gets a fixed percentage over what they paid for the drug, plus a flat dispensing fee. Sounds fair, right? Not really. It means if a generic costs $1.50, the pharmacy might get $2.50 total. But if the same drug costs $4.00 to buy (because the PBM set a high MAC), the pharmacy still only gets $2.50. So they lose money. And when pharmacies lose money, they stop stocking those drugs-or worse, they stop accepting that plan.

Independent pharmacies are feeling the squeeze. Between 2018 and 2022, over 3,000 closed. Why? Because they couldn’t survive on the reimbursement rates PBMs forced on them. Meanwhile, the three biggest PBMs-CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx-control 80% of the market. They set the rules. And they’re not in the business of helping small pharmacies stay open.

Generic Substitution Isn’t Always What It Seems

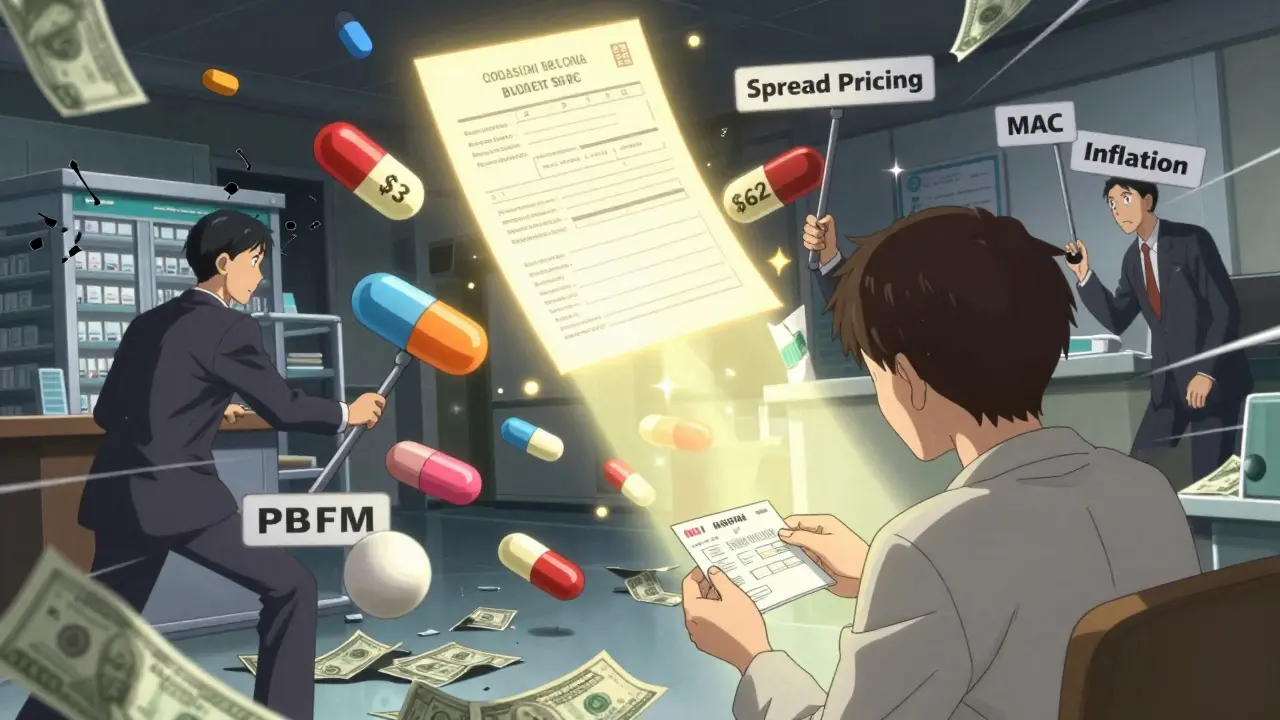

When you hear "generic substitution," you think: same drug, cheaper price. But that’s not always true. PBMs often substitute one generic for another-not because it’s cheaper, but because it pays more.

Research shows that two different generics in the same therapeutic class can have prices that differ by more than 20 times. One version of generic albuterol might cost $3. One version might cost $62. Both work the same. But if the PBM’s MAC is set at $60, the pharmacy gets paid $60, buys it for $4, and pockets $56. The patient pays their copay-maybe $10. The payer thinks they’re saving money. But the real savings? Gone.

Therapeutic substitution-switching from a brand to a different generic drug in the same class-is where real savings happen. The Congressional Budget Office found that switching brand-name drugs to generics in just seven Medicare drug classes saved $4 billion in 2007. But switching between different generics? Only $900 million. Why? Because the system rewards the wrong kind of substitution.

Why Transparency Matters

Most pharmacies don’t know what the MAC is for a drug until after they’ve dispensed it. Plan sponsors-like employers or insurance companies-often don’t know either. That’s intentional. Without transparency, there’s no accountability. PBMs can inflate MACs, pocket the difference, and call it "savings."

The Federal Trade Commission started investigating this in 2023. They found that some PBMs were using non-disclosed MAC lists to favor higher-priced generics. That’s not just unethical-it’s illegal under antitrust law. But enforcement is slow. And until PBMs are forced to reveal how they set prices, the game won’t change.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 started to crack the door open by requiring Medicare Part D to disclose pricing data. But commercial plans? Still hidden. Prescription Drug Affordability Boards in 15 states are now setting Upper Payment Limits to cap what can be paid for certain drugs. That’s a step forward. But it also risks making needed brand-name drugs harder to get if the cap is too low.

What’s Really Saving Money?

Let’s cut through the noise. The biggest savings don’t come from swapping one generic for another. They come from using the cheapest effective generic available-and making sure pharmacies are paid fairly for dispensing it.

Pharmacies need to be paid enough to cover their costs: labor, storage, inventory, compliance. A flat dispensing fee of $6-$8 is reasonable. But if the ingredient cost is manipulated to inflate profits, the system breaks.

Real reform means:

- Ending spread pricing by requiring PBMs to pass through the actual acquisition cost to pharmacies

- Making MAC lists public and standardized across all payers

- Paying pharmacies based on true cost, not inflated PBM pricing

- Encouraging therapeutic substitution-not just generic substitution-when clinically appropriate

Right now, the system rewards complexity. It rewards opacity. And it rewards PBMs-not patients, not pharmacies, not even the healthcare system as a whole.

The Bottom Line

Generic substitution was supposed to lower drug costs. And it has-when done right. But the reimbursement system has turned it into a profit engine for middlemen. Pharmacies are caught in the middle: they want to help patients save money, but they can’t afford to lose money doing it.

If you’re a patient, ask your pharmacist: "Is this the lowest-cost generic available?" If you’re a pharmacy owner, push back on contracts that don’t reflect true costs. If you’re a payer, demand transparency. The money is there to be saved. But only if the system stops hiding it.

The financial implications of generic substitution aren’t about pills. They’re about power. And until that changes, the savings will stay in the hands of the few-not the many.