Metformin & Contrast Dye Decision Tool

Your Metformin & Contrast Dye Guidance

This tool helps determine if you should continue or temporarily stop metformin before imaging procedures with contrast dye based on current medical guidelines.

When you’re on metformin for type 2 diabetes and need a CT scan or angiogram, a simple question pops up: Should you stop your pill before the contrast dye? For years, doctors told patients to hold metformin for days before and after any imaging test. But that advice has changed - and not just a little. The real risk of lactic acidosis from metformin and contrast dye is far lower than most people think. What’s actually dangerous isn’t the dye itself - it’s what happens when your kidneys can’t clear metformin fast enough.

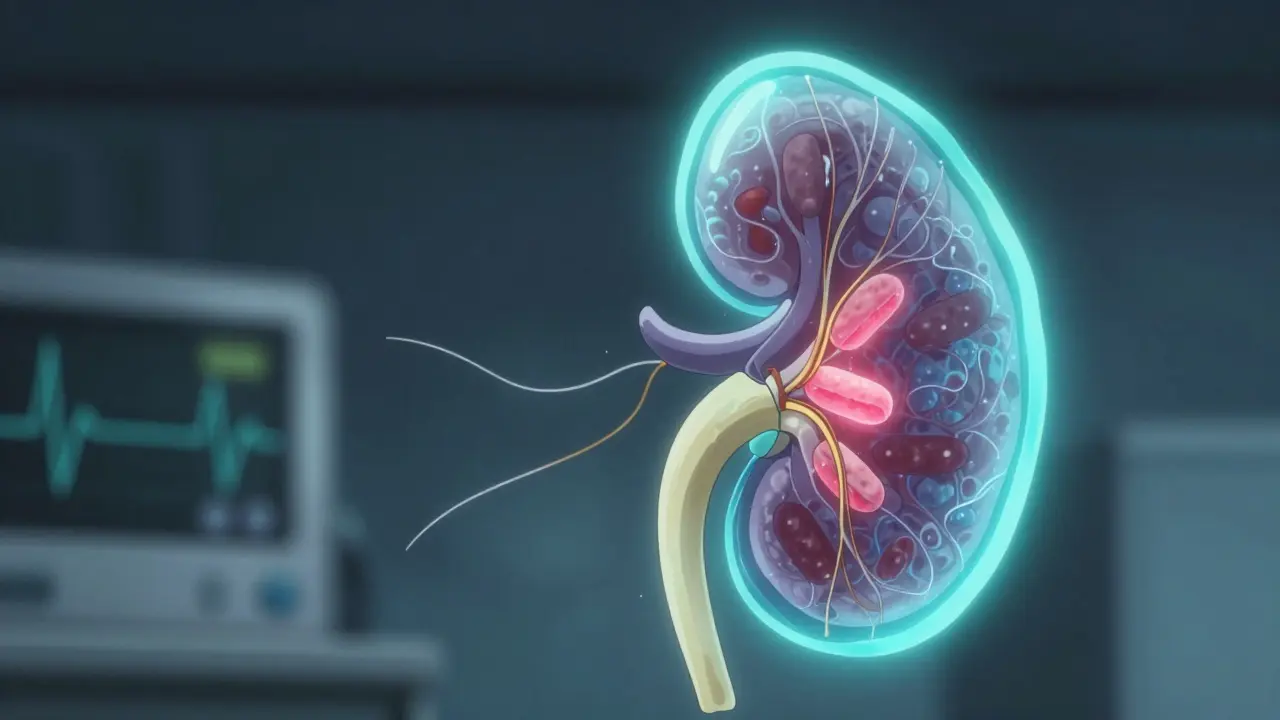

How Metformin Works - And Why Kidneys Matter

Metformin doesn’t lower blood sugar by making your body produce more insulin. Instead, it tells your liver to stop making so much glucose and helps your muscles use insulin better. It’s small, lightweight (165 Da), and doesn’t get broken down by your body. That means almost all of it leaves through your kidneys - unchanged. In healthy people, about 500 ml of blood is cleared of metformin every minute. That’s why it’s so safe for most diabetics.

But if your kidneys slow down - say, your eGFR drops below 60 mL/min/1.73 m² - metformin builds up. That’s where the risk starts. Not because metformin is toxic on its own, but because it interferes with how your cells use oxygen. It binds to mitochondria, the energy factories in your cells, and blocks the normal way they burn sugar. When that happens, your cells switch to anaerobic metabolism. That’s when lactate, a byproduct of inefficient energy production, starts piling up. Too much lactate = lactic acidosis.

What Is Lactic Acidosis? (And Why It’s Rare)

Lactic acidosis isn’t a common side effect. In fact, it happens in only 1 to 9 cases per 100,000 people taking metformin each year. Even in overdose cases, only about 9% lead to lactic acidosis. Compare that to the 150 million metformin prescriptions filled in the U.S. every year - you’re looking at maybe a few dozen cases total. Most of those cases aren’t from contrast dye. They’re from people with multiple risk factors: heart failure, severe infection, liver disease, alcohol abuse, or advanced kidney disease.

The symptoms are subtle at first - nausea, stomach pain, fatigue, fast breathing. Then comes confusion, low blood pressure, vomiting. By the time someone’s in the ER with acidosis, it’s serious. Mortality can hit 40% if not treated fast. But here’s the key: almost all these cases happen in people who already had severe illness. Not someone with a mild eGFR drop getting a routine CT scan.

The Old Rules - And Why They Were Wrong

Before 2016, the FDA told doctors to stop metformin before any procedure involving contrast dye - whether it was a simple IV injection or a complex heart catheterization. Patients had to go without their diabetes medication for 48 hours. That meant blood sugar spikes, hospital visits, and even diabetic ketoacidosis in some cases. Why? Because the fear of lactic acidosis was bigger than the evidence.

That changed when studies showed the risk was almost nonexistent in people with normal or mildly reduced kidney function. The FDA updated its label in 2016. Now, you only need to stop metformin if:

- Your eGFR is between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m²

- You have heart failure, liver disease, or drink heavily

- You’re getting contrast through an artery (like in a cardiac cath)

For everyone else - especially those with eGFR above 60 - you can keep taking metformin. No pause. No fear. No unnecessary blood sugar chaos.

IV vs. IA Contrast: The Big Difference

Not all contrast is the same. Intravenous (IV) contrast - the kind used in most CT scans - is diluted quickly in your bloodstream. Your kidneys filter it out in hours. Intrarterial (IA) contrast - used in procedures like angiograms or heart catheterizations - is injected directly into arteries under pressure. It’s more concentrated, hits the kidneys harder, and carries a higher risk of temporary kidney stress.

That’s why the guidelines treat them differently. For IV contrast, if your kidneys are working okay (eGFR >60), you’re fine. For IA contrast, even if your eGFR is 70, you still hold metformin. Why? Because the kidney insult from IA dye can be sharper and faster. It’s not about the dye being toxic - it’s about the speed and intensity of the hit.

What to Do Before and After Your Scan

If you’re scheduled for a scan, here’s what actually matters:

- Check your latest eGFR. If it’s above 60 and you have no other risk factors (no heart failure, no liver disease, no recent infection), keep taking metformin.

- If your eGFR is 30-60, or you have heart failure or liver disease, stop metformin the day of the scan. Don’t restart it until 48 hours after the procedure - and only if your kidney function hasn’t worsened.

- If you’re getting IA contrast (like a heart cath), stop metformin regardless of your eGFR. Restart only after 48 hours, with normal kidney values.

- Hydrate. Drink water before and after the scan. It helps your kidneys flush out the dye faster.

- Get a follow-up blood test for creatinine 48 hours after the procedure. That’s how you know your kidneys bounced back.

Don’t stop metformin just because you’re nervous. The risk of high blood sugar from missing doses is far more dangerous than the tiny chance of lactic acidosis.

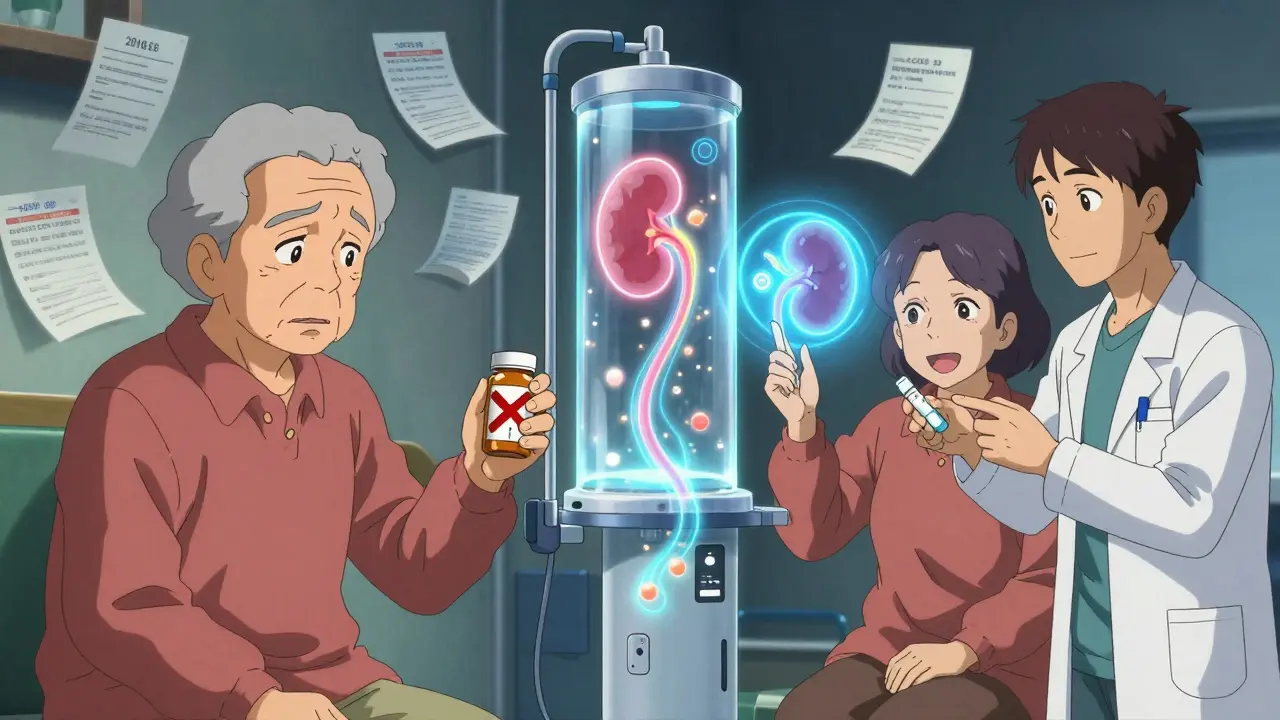

What If Lactic Acidosis Happens?

If someone develops lactic acidosis from metformin, it’s a medical emergency. Treatment isn’t about stopping the drug - it’s about removing it. Hemodialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is the gold standard. These machines clear metformin and lactate from the blood at the same time. Studies show that when patients get dialysis quickly, survival rates jump dramatically.

Most ICU cases involve people over 65 with sepsis, shock, or acute kidney injury. It’s not the contrast that caused it - it’s the combination of illness, poor perfusion, and metformin buildup. That’s why prevention is all about identifying risk before the scan, not panicking afterward.

Why the Guidelines Changed - And What It Means for You

The shift in guidelines isn’t just about science. It’s about avoiding harm. Holding metformin for days leads to hyperglycemia, which can cause dehydration, infections, and even diabetic ketoacidosis. In one study, patients who stopped metformin before a CT scan had 3 times more hospital admissions for high blood sugar than those who kept taking it.

The American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation now agree: unnecessary interruptions do more harm than good. The same goes for the American Diabetes Association. They’ve all aligned on one message: use risk stratification, not blanket rules.

As of 2021, about 65% of U.S. hospitals had adopted the updated guidelines. That’s progress - but many still follow the old, outdated protocols out of habit or fear. If your doctor tells you to stop metformin for a routine CT scan and your eGFR is 75, ask why. Bring up the 2016 FDA update. It’s your right to know the evidence.

The Future: Personalized Medicine and Genetic Risks

Researchers are now looking at why some people are more prone to lactic acidosis than others. Could it be genetics? Are there specific gene variants that make mitochondrial response to metformin more dangerous? Early studies suggest yes. In the future, we might see genetic screening before starting metformin - not for everyone, but for high-risk groups.

For now, the best tool we have is simple: know your eGFR. Know your risks. Don’t assume contrast dye is the enemy. The real enemy is ignoring your kidney function and letting fear drive decisions.

Metformin is still the first-line drug for type 2 diabetes for a reason. It’s effective, cheap, and safe - when used right. Contrast dye doesn’t turn it into a poison. Poor kidney function, illness, and outdated protocols do.

Can I take metformin before a CT scan with contrast dye?

Yes - if your kidney function is normal (eGFR above 60 mL/min/1.73 m²) and you don’t have heart failure, liver disease, or active infection. For IV contrast, you can keep taking metformin. Only stop it if your eGFR is 30-60, you have other risk factors, or you’re getting contrast through an artery.

Does contrast dye damage kidneys in people taking metformin?

Contrast dye can cause temporary kidney stress, called contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI), but it’s rare in healthy people. The real issue isn’t the dye damaging kidneys - it’s that if kidneys are already weak, metformin builds up. That’s when lactic acidosis risk increases. Hydration before and after the scan reduces this risk significantly.

How long should I stop metformin after contrast dye?

If you stopped metformin before the scan, wait 48 hours after the procedure before restarting - but only if your kidney function (eGFR) is stable or improved. Get a blood test at 48 hours to confirm. Don’t restart if your creatinine is higher than before.

Is lactic acidosis common with metformin and contrast dye?

Extremely rare. Studies show fewer than 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years of metformin use. Most cases occur in people with severe illness, not those getting routine imaging. The fear of lactic acidosis has been greatly exaggerated for decades.

What if I forget to stop metformin before a heart catheterization?

If you had a heart cath (IA contrast) and forgot to stop metformin, don’t panic. The risk is still very low if your kidneys are healthy. Inform your doctor immediately. They’ll monitor your kidney function and lactate levels if needed. Most people won’t have any issues - but it’s best to avoid the risk altogether in the future.