When you take a pill, you’re not just swallowing the medicine you need. You’re also swallowing a mix of other stuff-fillers, binders, dyes, preservatives-that don’t treat your condition but are still in there. These are called excipients, and for decades, they were treated like harmless bystanders. But new science is changing that. What if some of these so-called "inactive" ingredients are quietly affecting how your body reacts to the drug? Could they be making it work better, worse, or even causing side effects you didn’t expect?

What exactly are excipients?

Excipients are the non-active parts of a medication. Think of them as the scaffolding around the active ingredient. They help the drug stay stable, dissolve properly, taste less awful, or hold its shape in a tablet. Common ones include lactose (a milk sugar used as a filler), microcrystalline cellulose (a plant-based binder), magnesium stearate (a lubricant that keeps pills from sticking to machines), and tartrazine (a yellow dye). In most oral pills, excipients make up 60% to 99% of the total weight. That’s right-your pill is mostly not the medicine.The FDA lists around 1,500 approved excipients across all types of medicines, from injections to eye drops. Each drug typically uses 5 to 15 of them. The system was designed in the 1930s to standardize production, and for most of the last century, regulators assumed these ingredients were biologically inert. That assumption is now being questioned.

Why "inactive" might be a misnomer

A landmark 2020 study in Science tested 314 excipients against 44 biological targets and found that 38 of them showed measurable activity. That means they weren’t just sitting there-they were interacting with your body’s systems. Aspartame, for example, blocked the glucagon receptor at concentrations that can occur in the bloodstream after taking a tablet. Sodium benzoate, a common preservative, inhibited monoamine oxidase B, an enzyme linked to brain chemistry. Propylene glycol, used in liquid meds and chewables, affected monoamine oxidase A.These aren’t theoretical findings. The study showed that in normal therapeutic use, some people reach blood levels of these excipients that overlap with the concentrations shown to have biological effects in the lab. That’s not just a lab curiosity-it’s a real physiological interaction.

Dr. Giovanni Traverso, lead author of the study, put it bluntly: "The blanket classification of excipients as 'inactive' is scientifically inaccurate for a meaningful subset of these compounds."

Regulatory gaps and real-world consequences

The FDA allows generic drugmakers to swap out excipients as long as they don’t harm safety or efficacy. For most pills, that’s fine. But for injections, eye drops, and ear drops, the rules are stricter: the excipients must match the brand-name version exactly. Why? Because these routes bypass the body’s natural filters. A change in concentration or type can cause serious reactions.For oral drugs, though, the system is looser. That’s why in 2018, 14 generic versions of the blood pressure drug valsartan were recalled. The problem wasn’t the active ingredient-it was a new solvent used in manufacturing that created a cancer-causing contaminant called NDMA. That solvent wasn’t even listed as an excipient-it was a processing aid. But it still ended up in the final product.

And it’s not just contamination. Aurobindo’s 2020 application for a generic version of Entresto was rejected because they replaced magnesium stearate with sodium stearyl fumarate. In vitro tests showed a 15% difference in how fast the drug released at stomach pH. The FDA said that could affect how much of the drug actually gets absorbed-and that’s a big deal for a heart failure medication where precise dosing matters.

How generics handle excipient changes

Generic manufacturers want to save money and time. Using a different excipient can mean switching to a cheaper, more readily available ingredient. But proving it’s safe isn’t cheap. On average, it costs $1.2 million and takes 18 months to justify a new excipient to the FDA.There are three main ways to do it:

- Use an excipient already approved in the FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database (IID)-this works in 68% of successful cases.

- Run toxicology studies-required for 22% of new excipients.

- Build a "bridging" argument using pharmacokinetic data to show the drug behaves the same way-even with a different filler or binder.

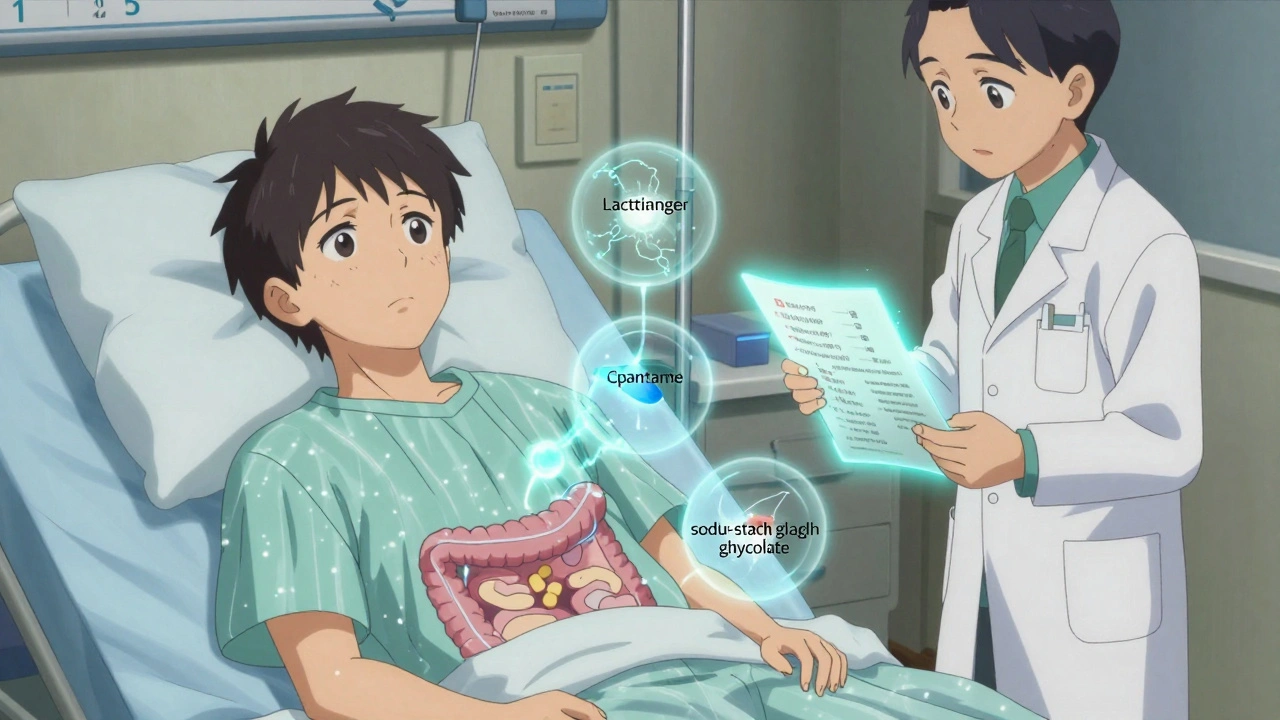

Teva’s 2021 approval of a generic version of Jardiance is a good example. They swapped sodium starch glycolate for croscarmellose sodium as the disintegrant. Bioequivalence tests showed nearly identical absorption: Cmax was 374 vs. 368 ng/mL, and AUC was 4,215 vs. 4,187 ng·h/mL. The FDA approved it because the data proved no meaningful difference.

Who’s at risk?

Most people won’t notice anything. But for some, excipients matter a lot. People with allergies to lactose or corn starch might react to fillers. Those with rare metabolic disorders can’t process certain sugars or alcohols. Diabetics need to know if a chewable tablet contains sugar or artificial sweeteners like aspartame. And for patients on multiple meds, additive effects from excipients could pile up.Even small changes can matter in sensitive populations. A 2023 FDA pilot program flagged aspartame and saccharin in orally disintegrating tablets after reports of hypersensitivity reactions in 0.002% of users. That’s a tiny number-but when you’re one of those people, it’s 100%.

What’s changing in 2025?

The FDA is finally catching up. In late 2023, they proposed updating the Inactive Ingredient Database to include predicted tissue concentrations for each excipient-something the 2020 Science study called for. They’re also developing a computer model to predict which excipients might interact with biological targets.By 2025, 30% of complex generic applications (like extended-release pills or combo drugs) will likely need extra safety studies, up from 18% in 2022. And a proposed rule change could require all new excipients to be screened against 50 high-risk biological targets before approval. That would add $500,000 to $1 million to development costs per new ingredient.

Some experts think this is overdue. Dr. Jane Axelrad, former FDA deputy director for generic drugs, says the system works fine for traditional pills-but not for today’s advanced delivery systems. Others, like PhRMA, argue that decades of safety data still back up most excipients. The FDA’s own adverse event database shows only 0.03% of reported side effects are definitively linked to excipients.

But here’s the problem: we’ve never systematically looked for these interactions before. Most adverse event reports don’t even list excipients. We’re flying blind.

What you should know as a patient

You don’t need to become a chemist. But you can be more aware. If you’ve had unexplained reactions to a medication-rash, nausea, headaches, or sudden changes in how you feel-ask your pharmacist or doctor if the excipients changed. Generic versions aren’t always identical. A change in binder or dye might be the culprit.Check the patient information leaflet. It lists all ingredients. If you’re allergic to dairy, look for lactose. If you’re diabetic, watch for sugars or artificial sweeteners. If you’re on a low-sodium diet, sodium benzoate or sodium starch glycolate might add up.

And if you’re taking multiple generics over time, don’t assume they’re interchangeable. Switching between brands might mean switching excipients-and that could matter.

The future of excipient safety

The pharmaceutical industry is moving toward smarter formulations. New delivery systems-like nanoparticles, gut-targeted coatings, and timed-release layers-rely on novel excipients. These aren’t just fillers anymore. They’re functional components.The International Pharmaceutical Excipients Council is working on setting concentration thresholds below which excipients can be considered inert. But critics say that ignores individual differences. One person’s safe dose could be another’s trigger.

The bottom line? Excipients aren’t just filler. They’re part of the drug’s story. And as drug delivery gets more complex, we can’t afford to ignore them anymore. The science is clear: what’s "inactive" isn’t always harmless. The system is catching up-but patients should stay informed.