When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, you might think generic versions instantly appear on pharmacy shelves. But in reality, it often takes years after patent expiration for the first generic to become available. Why? The gap between patent expiration and market launch isn’t just a delay-it’s a complex web of legal battles, regulatory hurdles, and corporate strategies that keep prices high and patients waiting.

The Real Timeline: From Patent Expiry to Pharmacy Shelf

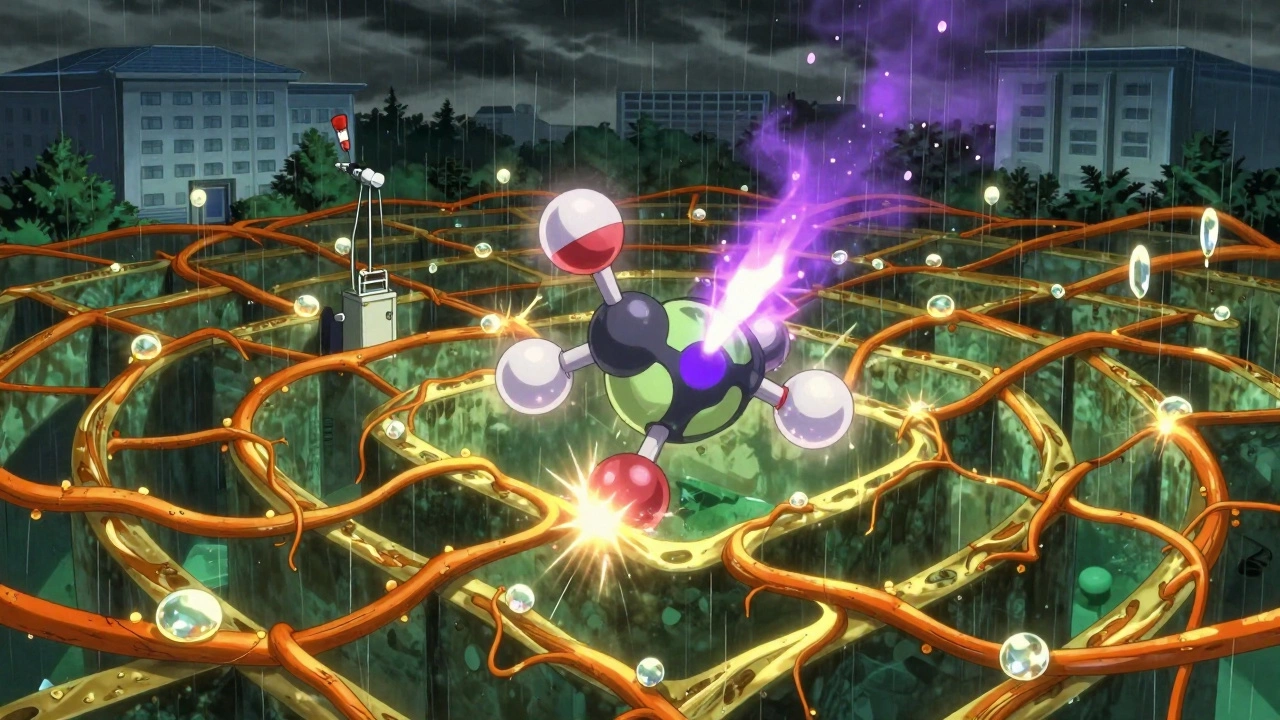

The standard pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the filing date. But here’s the catch: most of that time is eaten up during drug development. By the time a drug hits the market, only 7 to 12 years of patent life remain. That’s why companies rely on other tools to extend their monopoly. The FDA grants additional exclusivity periods that stack on top of patents. A new chemical entity gets 5 years of market protection. If the company runs new clinical trials for a different use, they get 3 more years. Orphan drugs-those for rare conditions-get 7 years. Add 6 months if they test the drug in kids, and suddenly you’ve got 13 years of protection before generics can even apply. Even after all that, the real race begins. Generic manufacturers must file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA. This doesn’t require repeating expensive clinical trials. Instead, they prove their version is bioequivalent-same active ingredient, same strength, same effect in the body. Sounds simple, right? Not quite.The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Rules of the Game

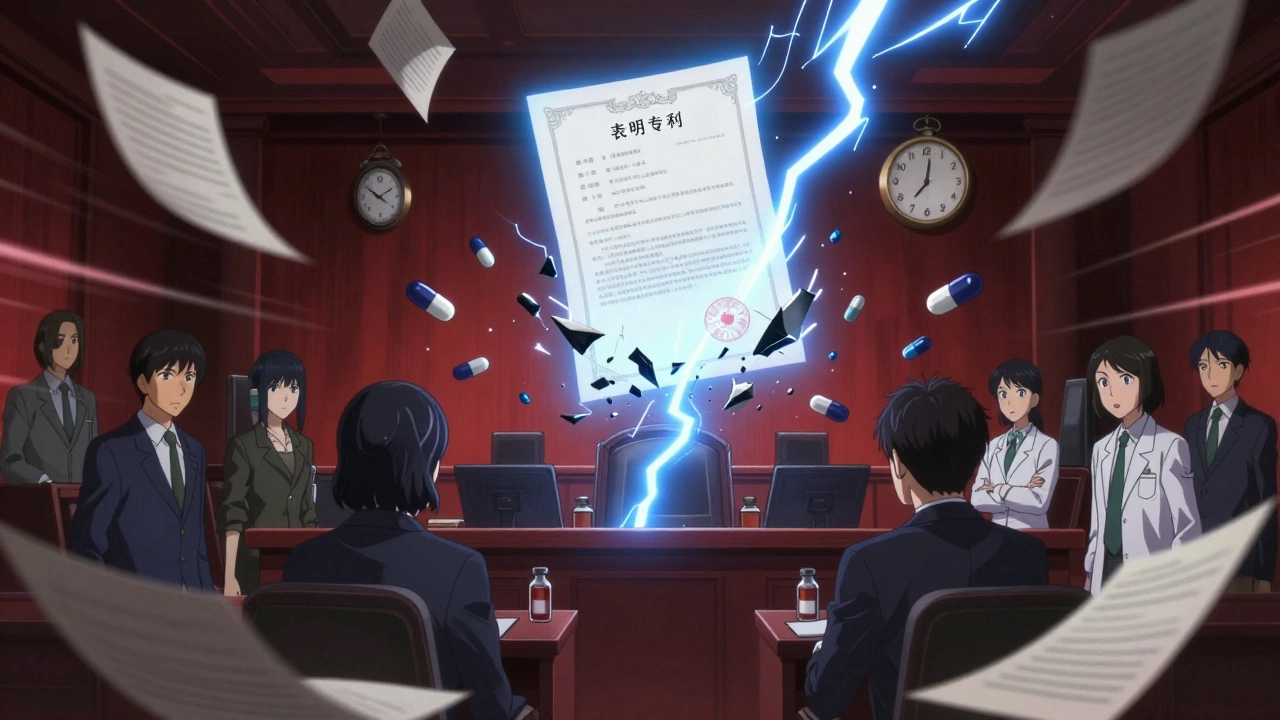

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act created the legal framework for generic entry. It was meant to balance innovation with affordability. But over time, it’s become a tool for delay. Here’s how it works: When a generic company files an ANDA, they must certify whether the brand-name drug’s patents are valid. If they say a patent is invalid or not infringed (a Paragraph IV certification), the brand-name company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA is legally blocked from approving the generic for 30 months. That’s the 30-month stay. But here’s what most people don’t realize: the 30-month stay is rarely the main delay. Studies show generic drugs typically launch 3.2 years after the 30-month stay expires. Why? Because the real bottleneck is patent thickets.Patent Thickets: The Hidden Barrier

Brand-name companies don’t rely on just one patent. They file dozens. A single drug might have patents covering the active ingredient, the pill coating, the manufacturing process, how it’s taken, even how it’s packaged. The FDA’s Orange Book lists these patents. On average, each drug has 14.2 listed patents. A drug with more than 10 patents takes 37% longer to get a generic version. Cardiovascular drugs, which often have complex formulations, face delays of 3.4 years after patent expiry. Dermatological products? Just 1.2 years. Why the difference? Simple: complex drugs are harder to copy. Generic makers need to reverse-engineer the drug, build a new manufacturing line, and pass FDA inspections-all while fighting legal challenges. If they’re the first to file a Paragraph IV challenge, they get 180 days of exclusive market rights. That’s a huge incentive. But it also creates pressure. If they can’t launch within 75 days of FDA approval, they lose that exclusivity.

Why Approval Doesn’t Mean Availability

The FDA approved 1,165 generic drugs in 2021. But only 62% of them hit the market within six months of approval. Why the gap? Some companies delay launch to avoid legal risk. Others can’t scale production fast enough. A few wait for competitors to enter first, hoping to undercut prices. And sometimes, the brand-name company uses “product hopping”-slightly changing the drug (new pill shape, extended-release version) and pushing patients to the new version. That keeps sales high while generics wait. The FTC found that 55% of delayed generic entries result from “reverse payment” deals: the brand-name company pays the generic maker to stay off the market. Courts now see these as anti-competitive. The Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that secret payments violate antitrust law. But they still happen-just more quietly.Who Controls the Generic Market?

The generic drug industry is dominated by three players: Teva, Viatris, and Sandoz. Together, they control 45% of the U.S. market. That concentration means fewer competitors to drive down prices quickly. High-revenue drugs-those making over $1 billion a year-face an average of 17.3 patent challenges. Lower-revenue drugs? Just 8.2. That’s why the biggest drugs take the longest to go generic. The financial stakes are too high for companies to give up control easily.What’s Changing? New Rules, New Tools

There are signs of progress. The CREATES Act of 2019 stopped brand-name companies from blocking access to drug samples needed for testing. The Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020 forced more accurate patent listings, cutting disputes by 32% in its first year. The FDA’s GDUFA II program aims to cut review times for complex generics from 36 months to 24. But only 62% of applications met that target as of mid-2024. The agency is also testing AI to speed up bioequivalence testing-potentially cutting development time by 25%. Still, the biggest problem remains: patent evergreening. A 2024 study found that 68% of brand-name drugs get at least one new patent within 18 months of the original expiring. These aren’t breakthroughs-they’re minor tweaks. But they’re enough to keep generics locked out.

The Cost of Waiting

Every year a generic is delayed, U.S. healthcare pays more. The Congressional Budget Office estimates a one-year delay on a top-10 drug costs Medicare $1.2 billion. In 2023, generic drugs saved the system $373 billion. That’s money that could go to more patients, better care, or lower premiums. The irony? Generics make up 92% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but only 16% of total drug spending. The system works-if generics can get here on time.What Patients Can Do

If you’re on a brand-name drug nearing patent expiry, ask your pharmacist: “Is a generic coming?” They can check the FDA’s drug database or the Orange Book. If one’s approved but not available, ask why. Sometimes, it’s just a supply issue. Other times, it’s a legal hold. Switching to a generic isn’t always possible right away. But knowing the timeline helps you plan. And if you’re paying out-of-pocket, waiting a few months might save you hundreds.The Bottom Line

Patent expiration isn’t the finish line-it’s the starting gun. The real race is between corporations, regulators, and the law. And right now, the system favors the brand-name companies. The delays aren’t accidents. They’re designed. But change is coming. With more transparency, fewer reverse payments, and smarter regulation, the gap is slowly closing. For now, patience is still a requirement. But awareness? That’s your power.Why don’t generic drugs appear immediately after a patent expires?

Generic drugs don’t launch right away because brand-name companies often file lawsuits to block entry, and generic manufacturers must navigate complex regulatory steps. Even after patent expiration, other exclusivity periods, patent thickets, and legal stays can delay approval and market launch for months or years.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generics?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the ANDA pathway, allowing generic makers to prove bioequivalence without repeating clinical trials. It also introduced the 30-month stay and 180-day exclusivity for first filers. While designed to balance innovation and access, it’s now used strategically by brand-name companies to delay competition.

What’s a patent thicket, and why does it matter?

A patent thicket is when a drug has many overlapping patents covering different aspects-like the chemical, the pill coating, how it’s made, or how it’s used. These make it harder and slower for generics to enter because they must challenge each patent individually. Drugs with over 10 patents take nearly a year longer to reach the market.

Do reverse payment settlements still happen?

Yes, but less openly. After the Supreme Court ruled secret payments violate antitrust law in 2021, companies now use indirect deals-like exclusive distribution rights or licensing agreements-to delay generics. The FTC estimates these still delay 45% of potential generic entries.

How long does it take to get a generic approved after filing an ANDA?

The FDA’s average review time for an ANDA is 25 months and 15 days. For complex drugs-like injectables or inhalers-it can take over 3 years. Even after approval, manufacturers may delay launch due to manufacturing issues, legal risks, or market strategy.

Can I ask my pharmacist if a generic is coming?

Yes. Pharmacists can check the FDA’s Orange Book and drug databases to see if a generic has been approved or is pending. If one’s approved but not yet available, they can often tell you why-whether it’s a supply issue, legal hold, or manufacturer delay.

Are biosimilars treated the same as generic drugs?

No. Biosimilars are copies of biologic drugs-complex proteins made from living cells. They follow a different pathway under the BPCIA and take much longer to develop-on average 4.7 years after the original patent expires. They also face more regulatory scrutiny and patent challenges than small-molecule generics.